THE EXHIBITIONS THAT DEFINED THE 2000S

Christian Marclay’s The Clock

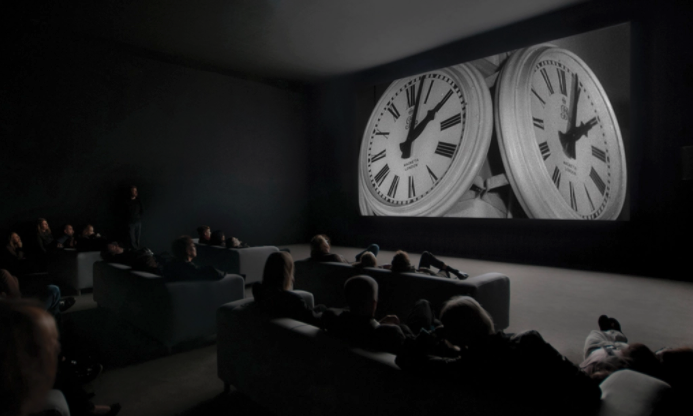

Christian Marclay’s twenty-four-hour video installation, The Clock, had its 2010 premiere at White Cube in London and went on to win a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2011. Comprising thousands of clips appropriated from films and television shows (Safety Last!, Gaslight, Double Indemnity; “Mission Impossible,” “ER,” “The X-Files”) produced over the previous hundred years, the compilation functions as a chronometer in itself, with depicted clocks and verbal references corresponding to the time at the viewer’s own location. Marclay’s obsessive montage was assembled over some two years in collaboration with six research assistants; Marclay edited this high-low material (Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet alongside forgettable commercial films) using a single aspect ratio. Collaborator Quentin Chiappetta provided expert linking of soundtracks, a key to the work’s immersive and eerily engaging polyvocal quality. Famously, The Clock holds spectators’ attention in a relentless grip through its suspension of resolution, stringing action along between and among various truncated scenes and gestures: a woman walks to a door in one scene and, after a cut, a couple exits a building; a man looks up from his watch and, in a subsequent shot, the camera scans an unrelated landscape.

The Clock has been compared to other works of appropriation-based durational video such as Douglas Gordon’s 1993 installation 24 Hour Psycho, a silent projection that extends the Hitchcock film into an all-day affair. However, The Clock’s treatment of time is quite different from that embraced by Gordon—or, for that matter, such auteurs of slowed-down cinema as Andy Warhol (Sleep, Empire) or Wang Bing (West of the Tracks). Over the course of his daylong video, Marclay does not make his viewer feel the lugubrious infinity of the here-and-now so much as its unbearable brevity and disconcerting ineffability.

“This is a time machine,” intones Rod Taylor in an excerpt from George Pal’s 1960 adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel that appears at around 5:45 PM in The Clock. The statement is at once wittily overdetermined and slightly oppressive: sitting rapt in a dark gallery before a 12-by-21-foot projection, The Clock’s viewers know exactly what time it is, even as they observe the present moment slipping unceasingly away without the traditional cinematic payoff of a twist in the plot or, perhaps, a conclusion.

An immensely popular yet ambivalent commentary on the legacy of movies and television in the internet age, The Clock illustrates the technological mediation of contemporary life—in all its thoroughness, speed, and hypotactic accumulation of images. The aesthetics of the database take over, and the video’s thousands of protagonists each have only seconds to distinguish themselves. As director and critic Chris Petit opined, it’s like “YouTube for gallery space.”

—Lucy Ives

Date: December 8, 2020

Publisher: Art in America

Format: Print, web

Genre: Nonfiction

Link to the essay.

On site.

View of Christian Marclay’s exhibition "The Clock," at White Cube, London, 2010. Courtesy White Cube, London, and Paula Cooper, New York.