IN 1971, BOTH THE USPS AND THE TERM “MAIL ART” WERE BORN

The first widely circulated use of the term “mail art” in print occurred in the title of an exhibition catalogue: Mail art—Communication à distance—Concept. This publication was released in November of 1971: the same year that mail processing in America was transformed by the founding of the quasi-corporate United States Postal Service. The exhibition took place on the other side of the Atlantic, as part of the seventh Biennale de Paris, and was the brainchild of a French master’s student in his early twenties. A year prior, curator Marcia Tucker had organized a show with Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondance [sic] School at the Whitney Museum of American Art, featuring postcards, letters, and drawings from 106 participants, though the survey didn’t use the term “mail art.” Indeed, artist John Held Jr. recalls that the exhibition was presented without “standard curatorial comment” altogether. The French show is significant because it foregrounds the role of the postal service itself—which looms in the background, if not the foreground, of many postal works. With the USPS’s crucial role in this year’s election, it is instructive to revisit this exhibition that highlighted the roles postal workers play in artistic production.

In the US, the transformation of mail in July of 1971 was brought about by an act of Congress that converted the former federal Post Office Department into a government-owned company that was expected to generate enough revenue to be self-sustaining. Previously, for some two centuries, American taxpayers had funded the POD. The reorganization into this autonomous entity was agreed to by unions and the government after postal employees, primarily led by Black workers, had successfully engaged in dramatic nationwide wildcat strikes in March of 1970. In New York City, where the strikes began, stocks fell and some feared that the market would close altogether. After unsuccessfully ordering postal workers back to their jobs, President Nixon summoned the National Guard to the Big Apple. However, the Guard and other miscellaneous military personnel—deployed in a mission dubbed Operation Graphic Hand—were unable to restore normal mail service. The 1970 strikes protested pay so low that many mail carriers and other workers required second jobs or received welfare assistance. In return for collective bargaining rights and long-overdue raises, postal worker unions accepted that their place of work would be run as a business—a Nixon-administration idea that they had earlier resisted. According to American mail historian Philip F. Rubio, Frederick Kappel, who had headed AT&T before becoming USPS chairman from 1972 to 1974, saw the resulting Postal Reorganization Act as a first step toward privatizing the mail.

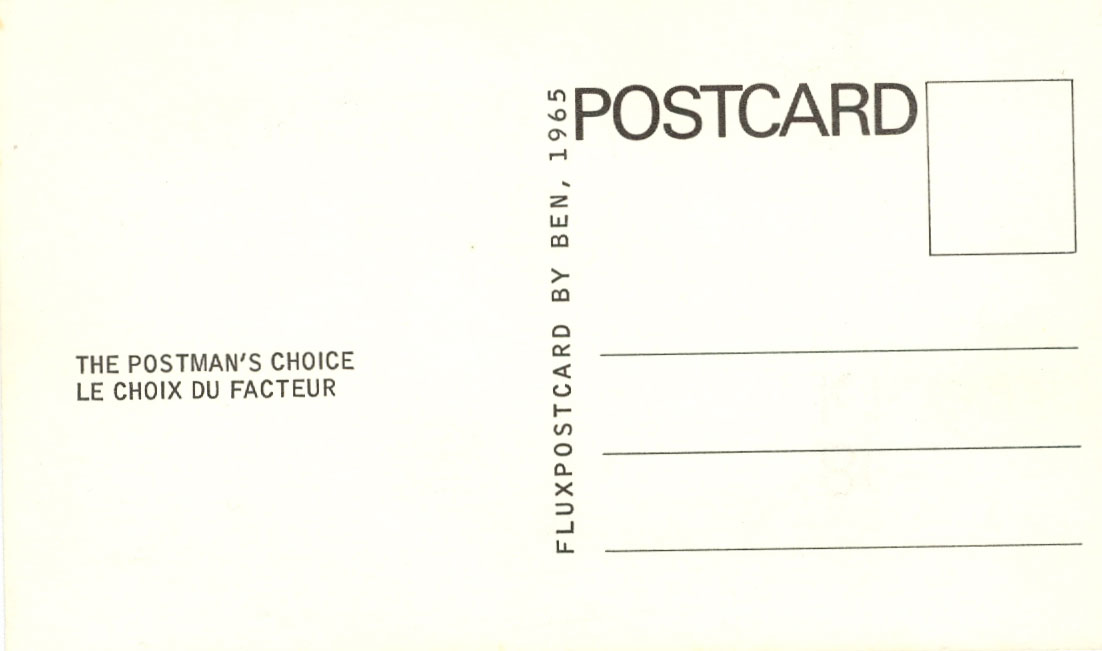

Meanwhile, in France, the youthful scholar Jean-Marc Poinsot had become fascinated by what he perceived as an overlooked mode of artistic production, the envoi, literally “a sending,” and here, specifically, an item sent by an artist in the mail. Poinsot’s curiosity was roused by artist-friends including Christian Boltanski, Jean Le Gac, and André Cadere, with whom he was then socializing as he completed his dissertation at Nanterre. Wanting to bring greater attention to the envoi form, as well as to a growing body of work by contemporaries, Poinsot began soliciting contributions from artists in and around his network of acquaintances, writing to the Swiss Fluxus artist Ben Vautier, among others, for advice. As historian Klara Kemp-Welch notes, Poinsot explained to Vautier, who preferred to be called simply “Ben,” “Envois are only to be found in the possession of their recipients and, as they are not visible in magazines, galleries, or museums, I am obliged to return to their source.” Poinsot’s major finding about mail art seemed to be that “postal communication is a form of long-distance communication, and thereby the aesthetic object is modified both in its form and in its presentation.” Although Poinsot does not elaborate regarding this “modification,” it is clear that many artists considered the bureaucratic processes and official material and graphic formats related to the mail a significant part of the artworks they sent to one another.

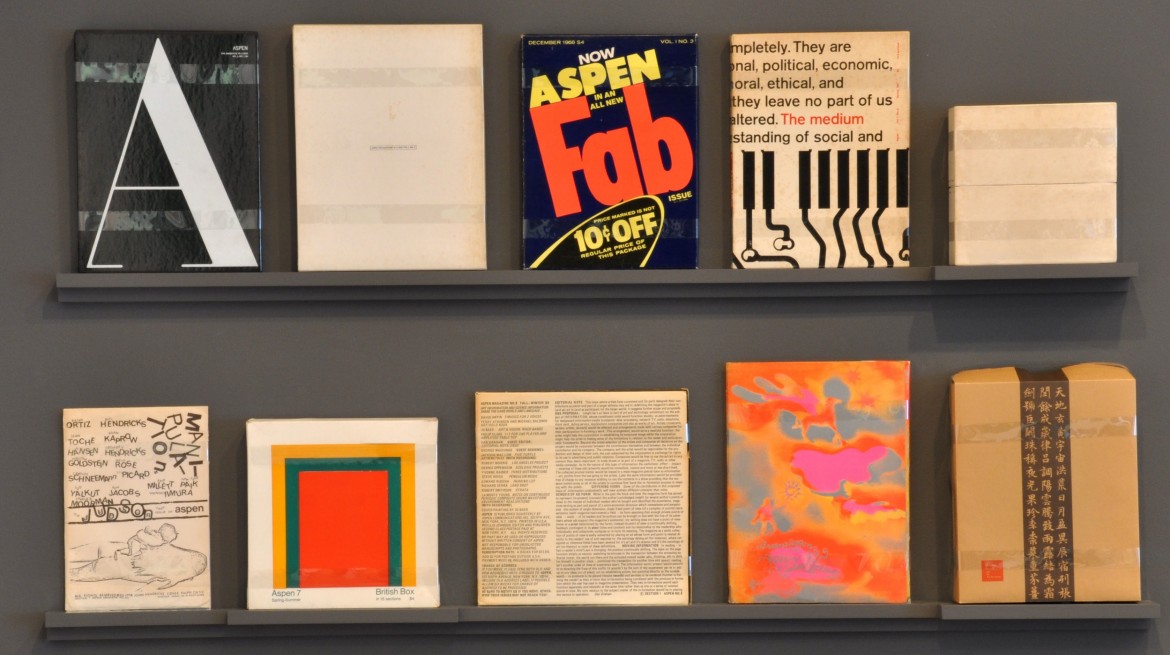

The artist Ken Friedman, a Fluxus participant, has written of his experience with postal regulations and his enjoyment of the challenge of trying to send via the USPS “objects that were difficult or perhaps impossible to mail,” such as large chairs. As Friedman notes, this activity required not only precise knowledge of acceptable dimensions and packaging rules but an ability to negotiate with postal workers, who themselves became more intimately involved in the work of art in the case of a bulky or unusually shaped package—perhaps more to their annoyance than creative fulfillment. Also worth considering is the death of Aspen, the “first three-dimensional magazine,” edited by Phyllis Johnson, formerly a writer and editor for Women’s Wear Daily and other periodicals. Aspen met its end in 1971 (the year of Poinsot’s exhibition and the creation of the USPS), after six years of operation and ten issues. The project lost its second-class mail license due to the Postal Service’s ruling that Aspen was not a magazine but rather a “non-descript publication” that was “unclassifiable; belonging, or apparently belonging, to no particular class or kind.” Without a second-class license, it was prohibitively expensive to mail subscribers the experimental magazine—a box containing thematically organized media items. Both of these examples point up the simultaneous freedom and banal constraint represented by the postal service, particularly in regard to visual art. It is clear that artists associated with mail art were interested in the possibilities of the post as a means of circumventing the formality of galleries and museums, of establishing intimacy across distance, and of engendering surprise and joy in one another—not to overlook the general cheapness of this method of sharing work, particularly meaningful in the US, where artists have long been unable to expect much assistance from their government. We might also add that mail art could (and can) be a form of political resistance, establishing vocabularies and codes that would be significant to recipients but meaningless to state censors or other less-than-welcome readers. All the same, artist Yves Klein, who created a series of stamps in his signature blue for exhibition invitations in the 1950s, had to be sure that his self-made postage was regulation size. At the post office, he not only paid the established price for mailing but also tipped the postal clerk to postmark his diminutive paintings. This was not an economic exchange of the same order as one with a gallerist, collector, or museum acquisitions representative, but it was nevertheless a necessary negotiation. And all those who mail artworks (or, anything at all, for that matter) engage in such apparently mundane and yet official, regulated, and theoretically uniform transactions.

In his quest to make an array of (previously semi-private) mailed artworks visible on the occasion of the 1971 Biennale, Jean-Marc Poinsot turned not only to practitioners associated with Fluxus, but also to artists who were participating in slightly older networks: the francophone Nouveaux Réalistes and Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondance School, a network of artists who engaged in a sort of postal “dance.” The responses to Poinsot’s invitation were overwhelmingly numerous and varied, surprising and delighting him (he had a good mail day every day for several years, he claimed). The project, which was originally conceived as taking the form of a book exclusively, grew by chance when Poinsot was invited to contribute to the section of the 1971 Biennale devoted to conceptual art. Poinsot selected forty artists—among whom were such well-known figures as Johnson himself and On Kawara—to be included in the book as well as in the exhibition. He also designed a participatory component: visitors to the installation were able to mail their own letters using a stamp dispenser and a working post box and were invited to make phone calls using a provided stall and to employ photocopiers as well as a photo booth to reproduce traces of their presence in the cavernous gallery in the Parc Floral de Vincennes. The exhibition, which included a selection of works by Eastern European artists, traveled to Belgrade in January of 1972 and to Zagreb the following March.

One of the more unexpected qualities of Poinsot’s exhibition was its inclusion of a number of artists from the Soviet bloc, where state control of media and other institutions gave their envois a different valence from that of pieces produced in the West. Some of these works were designed to encode messages in the guise of “nonsensical” aesthetic experimentation; others were subject to redaction and other forms of institutional mark-making and censorship. Mailings by the Hungarians Gyula Konkoly and Endre Tót as well as the Czechoslovak Petr Štembera were included—with each artist engaging in his own form of pointed evacuation of meaning from his missives: Konkoly simply reproduced a rejection letter from a grant-making organization in Paris, Tót opted for a series of O’s in lieu of words, and Štembera offered a grouping of blank pages. Tót additionally made use of a poignant artist’s stamp that proclaimed the reason for his communications: “I write to you because I am here and you are there.” When the show arrived at the Galerija Studentski Centar in Zagreb, the gallery director, Želemir Koščević, elected not to open the crate containing all of the envois but rather exhibited the container itself as-was, documenting this artful decision by having himself photographed standing before and atop it. As Kemp-Welch writes, Koščević believed that the exhibition of the works at the Biennale in Paris had “marked the end of the life of this idea,” and that he was therefore exhibiting “the postal package as postal package.” So concluded the circulation of Poinsot’s precocious and unusually engaged master’s thesis.

As Gérard Régnier, a critic and later the director of the Picasso Museum, wrote under his penname “Jean Clair” in a succinct and illuminating preface to the exhibition catalogue, once an object or practice is considered art—“consecrated to, confiscated by a museum” —it then loses its everyday role, becoming, in a sense, “superbly useless.” Thus, there was some acknowledgement that a number anti-institutional artistic practices were receiving their first institutional recognition by being included in a traveling exhibition and a publication with a print run of 1,500 copies. Yet, Poinsot was more concerned with loftier questions in his introduction. Writing in the tortured style of a diligent graduate student, he focused on the question of how meaning relates to artistic form, citing Marcel Duchamp as a paradigmatic example of an artist who generated a “self-enclosed” world of signification, in which the art object is at once a “means of communication and . . . a study of the mechanisms of communication.” Poinsot offered Duchamp’s exploration of postal dynamics in Rendez-vous of [Sunday] 6 February 1916, a series of postcards narrating a meeting as well as explaining some of Duchamp’s own works, as a canonical example of art commenting upon distribution networks. That Duchamp gave these postcards by hand to his friends, Louise and Walter Arensberg, much-noted collectors of modernist works, might be seen as further proof that the artist intended to comment on the channels that enable art to circulate and survive. Poinsot, for his part, was very concerned with how an artwork intended for a private recipient might become public, “the means by which,” as he wrote, “we become conscious of [these artworks].” He considered that artists might at some point decide to sell some of the works they received by mail, but would do so at “risk of distorting their meaning.”

As we know, this episode, far from representing the conclusion of mail art, was merely one in a long series of actions and events that are ongoing today. Many artists with varied practices, from Yoko Ono to Joseph Beuys to K8 Hardy, have engaged in reciprocal mail-art practices, defying the stereotype of the isolated, incommunicative genius. A visit to the post office can indeed seem so ordinary (or, so distressingly, ploddingly time-consuming, depending on the time of year and one’s location) that it can be easy to forget the incredible benefit that a state-run, non-market-driven post represents. In the United States, where cuts in service and compensation have been the norm since 2011 and where the federal government has repeatedly attempted to privatize the service since the Kappel Commission recommended that the postal service be “self-supporting,” some citizens may forget that an inexpensive and ubiquitous mail system is essential. As commentators and historians have pointed out with increasing frequency, the United States Postal Service continues to be the only delivery service that goes everywhere in the United States, “to patrons in all areas” and “all communities,” as Title 39 specifies. This law also says, rather plainly, “The costs of establishing and maintaining the Postal Service shall not be apportioned to impair the overall value of such service to the people.” Meanwhile, FedEx and UPS—whose options that are significantly more price-impaired—deliver, in combination, approximately 130 billion fewer pieces of mail within the United States than the USPS each year. This is a figure that takes a moment to sink in.

Although much is currently being made, and very rightly so, of Trump-campaign donor Louis DeJoy’s June 2020 ascent to the position of postmaster general—along with his leaked plans for austerity, slowing of service, and firing of senior USPS officials—DeJoy’s ambitions are not entirely original. For nearly fifty years the USPS has maintained its awkward status as a semi-public/semi-private “self-supporting” corporate entity. Its ability to continue on this path has been challenged not just by the advent of email and other forms of electronic communication, but by oversight issues, including a provision in a 2006 law that requires the USPS to fund employees’ future retirement medical benefits in advance, which has been blamed, if controversially, for many of its financial woes. The Great Recession did significant damage, and the company has not turned a profit since 2007. In the context of art, it is difficult to imagine On Kawara notifying a wide array of individuals of the time at which he woke up at a rate of $12.40 (intrastate delivery to a residential address by UPS) or $8.50 (by FedEx “One Rate” envelope) or more per missive. Recall that a first-class “Forever” stamp that will cause your envelope to be conveyed anywhere within the United States, most likely in a matter of days, is currently priced at 55 cents. Perhaps now is a good time to stock up.

On site.

Cover of the January‒February 1973 issue of Art in America, which featured David Zack’s essay “An Authentik and Historikal Discourse on the Phenomenon of Mail Art.”

Ben Vautier: The Postman's Choice, 1965, postcard, 3 5/16 by 5 9/16 inches.

View of the exhibition “Aspen Magazine: 1965-1971,” 2016, Whitechapel Gallery, London.