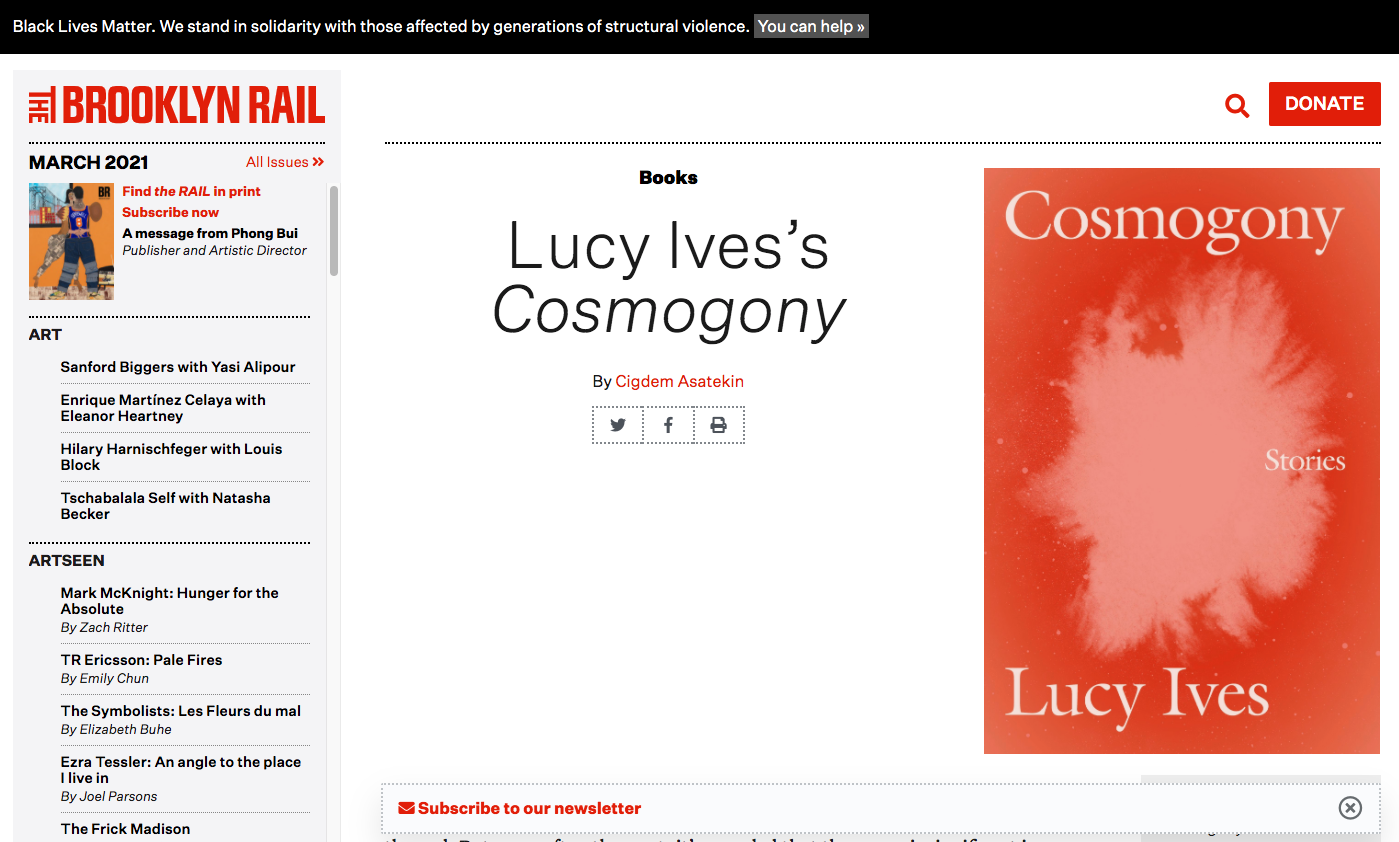

Lucy Ives’s Cosmogony

By Cigdem Asatekin

There are moments in life that one thinks will add up to something decisive in the end. But more often than not, it’s revealed that they were insignificant in the grand scheme of things—assuming there is one. Lucy Ives’s debut collection of short stories, Cosmogony, is made up of these kinds of moments: a meme you thought would get a few laughs, a tedious coffee date with an artist, a pun you remember from years ago, a sculptor who is a plagiarist but also your mom’s friend, a mysteriously replaced bodega cat.

Cosmogony consists of 12 stories, every single one a profound narrative that takes a different form. When they get surreal, they are reminiscent of dream sequences. Even when they don’t, there is the slight hint of something unearthly, or at least uncanny throughout the book. Yet they all sound so familiar. On a sunny day one can, in a moment’s flash, time travel to visit an old relationship like in “The Volunteer.” One can feel the world “attempting to recompose itself,” growing as soft as a blanket, after the headrush of newfound love similarly to Will and Jamie in “The Poisoners.” Moments are written in such clarity and tact that an angel on earth working in IT, or a woman who lives at the bottom of the ocean taking the A train feels completely reasonable. Lucy Ives writes prose with the poetry inherent in her words, making the natural unnatural and the monotone fascinating, filtering and projecting the reality through the eyes of a poet. While doing so, she unveils parts of human nature through the book’s ostensibly mundane events, like the worldly games of tennis and Murder, or a proverbially unhealthy relationship of a woman and her mother. Some stories include marriage, specifically early marriage, and some bleak aspects of personal, familial, and professional relationships of contemporary living. Darkness finds its way through these cracks. “This is the way things work,” writes Ives in one of those moments, “not through vision but through blindness.”

When Ives writes about art, biographical or historical information finds its place gracefully within the fiction without being mere footnotes. Her reflections provide the basis of a delicate understanding of art criticism in relation to creative writing. Ives’s previous novel, Loudermilk, had a similar approach to longform art writing, and works of art are essential to Cosmogony as well. Their influence permeates all, even if they are only peripheral mentions. A Frida Kahlo portrait, an incredibly “weird” art object of mystery presented to a copywriter in “The Care Bears Find and Kill God,” a violent novel by Joyce Carol Oates, and works of sculptor Louise Nevelson meet halfway with Craigslist ads and a framer’s love affair. Meditations of Gottfried Leibniz (and his theory of monads) and Walter Benjamin (and his essay on human speech) are weaved seamlessly into the narrative, connecting the book’s insightful writing to its author’s wit. In “A Throw of the Dice,” there is a perceptive mention of shipwrecks in art in connection to Stéphane Mallarmé that complements the first-person narration of a writer who translates Symbolist poetry. In the uncanny world of Cosmogony, this makes perfect sense with story-within-a-story writings of erotica. Ives also plays with form as one story, “Scary Sites,” consists only of a back-and-forth conversation, and “Guy” is written in the style of a Wikipedia entry. The Internet’s underlying dominance in daily life has its marks on Ives’s writing as well. From its myths, terms, specific language and memes, there is no escape. “The Care Bears Find and Kill God” walks away from an expected climax by an unexpected mention of a funny image the narrator saw online. “It’s a joke,” she says.

The characters and their surroundings are recognizable to anyone in contact with any metropolitan art scene. Like Ives’s previous novels Loudermilk and Impossible Views of the World, Cosmogony emits the almost privileged feeling of being an insider of the art world. For an individual who is actually in the arts, it’s thrilling: Reading “Trust,” it was certain that once upon a time I was the one who had coffee with the artist who produces x. But having worked at an art gallery isn’t necessary to feel the human connection and sense of belonging conveyed by Ives. In the middle of a world full of the similarly absurd, I have been so many of these characters. I had found a well-hidden FedEx package which was an actual miracle. I sent images of numerous bodega cats to friends. I may have even dated a demon for a little bit. He was just some guy.

On site.