CRITICAL EYE: PUBLISHING AMID THE MUSEUM’S RUINS

During a 2012 conversation at Art Basel, artist Adam Pendleton told curator Jenny Schlenzka, “I have a copy machine. It’s the queen of my studio.” The remark was offhand, yet revealing and generous. Pendleton, who is in his mid-thirties, has a multidisciplinary practice encompassing painting, printmaking, book arts, performance, filmmaking, sculpture, and event organizing. At times he describes himself as a conceptualist but, eschewing rigid emphasis on systems and nonrepresentational strategies sometimes associated with the term, he has also spoken of “a kind of philosophy of being” in relation to the images, spaces, and occasions he creates. In all his output, Pendleton works with preexisting language and print materials; as he said in a 2012 interview with Thom Donovan in BOMB, “I am constantly lifting words, sentences, images from a wide variety of sources.” A photocopier was not obviously involved in The Revival (2007), commissioned by the Performa festival in New York, for which Pendleton orchestrated a secular sermon with a full choir by appropriating language from experimental poetry, political speech, and traditional gospel songs. Yet, the duplicating device stands as a possible metaphor and accomplice for a work such as this, in that it enables the rapid recontextualization and repetition of words otherwise located on the pages of books in Pendleton’s extensive library.

Curator Adrienne Edwards argued in her 2015 Art in America essay “Blackness in Abstraction” that Pendleton employs reproductive technologies—Adobe Illustrator, silkscreen, as well as a Xerox—to emphasize “blackness as material, method and mode, insisting on blackness as a multiplicity.” In keeping with this ability to move from the material to the conceptual and back again, Pendleton is known for a photocopied compilation of writings by Hugo Ball, Amiri Baraka, W.E.B. Du Bois, Sun Ra, Adrian Piper, and Gertrude Stein, among others, that he published in 2017 with Koenig Books as The Black Dada Reader. These texts evince Pendleton’s larger Black Dada methodology, which combines influences from both Ball’s 1916 Dada Manifesto and “Black Dada Nihilism,” a 1964 poem by Baraka (then LeRoi Jones). Pendleton’s Black Dada is on the one hand a return to the politically charged nonsense of the Zurich Dadaists and, on the other, an exploration of the term Black as an “open-ended signifier,” as he has said. Black Dada is at once revolutionary and archival, allowing Pendleton to reflect on anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and decolonial political movements, including Black Lives Matter and Occupy, along with philosophical and literary writings. The photocopier has an obvious practical role in this undertaking, particularly given that Pendleton first produced the reader for personal use. Yet the device stands as an allegorical presence, too—indicating Pendleton’s commitment to a nonlinear mode of historiography that allows for repetition, nesting, and transposition, among other transformations and dilations.

The year 2021 is turning out to be significant for Pendleton. His installation As Heavy as Sculpture (2020–21) appeared in the lobby of the New Museum from February to June as part of the exhibition “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” curated by the late Okwui Enwezor. A montage of black-and-white imagery and text covering the walls, As Heavy as Sculpture layered reproductions of photographs of political events in Africa, masks, and sculptures, with iterations of language drawn from Black Lives Matter protests, including the acronym ACAB (for All Cops Are Bastards, also represented numerically as 1312). In September, DAP released an artist’s book by Pendleton related to the installation. Titled Adam Pendleton: As Heavy as Sculpture, the volume permits sustained, close consideration of the words, letters, numbers, and images Pendleton selected and sometimes partly painted over for the installation, encouraging a mode of reading in which one considers what cannot be seen as much as what is visible. Also published in September, by DABA and Koenig Books, was Adam Pendleton: Pasts, Futures, and Aftermaths, a revisitation of the format of The Black Dada Reader, with a new selection of texts, including writings by Sara Ahmed, Clarice Lispector, and Malcolm X, among others. For his solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which opened in September, Pendleton published another anthological reader, Adam Pendleton: Who Is Queen?, which functions as the show’s catalogue.

That Pendleton is publishing two new critical anthologies this fall points to a need to reframe the experience of viewing art, one that is particularly urgent in light of current anti-racist and anti-capitalist movements, as well as efforts to reform the labor and collecting practices of museums, along with the composition of their boards of directors. Pendleton’s readers are, in effect, new narratives of the history of art, bibliographies and syllabi, personal records of research and learning, spiritual autobiographies, and guides to contemporary politics. Like As Heavy as Sculpture, they generate original, inter-media, transdisciplinary modes of reading; in Who Is Queen?, for example, one reads the poet Simone White with and against curator Kynaston McShine with and against critic Lauren Berlant with and against composer Julius Eastman, to name but a few of the figures present. All of Pendleton’s selections appear as photocopied texts—“poor images,” in Hito Steyerl’s sense—and he has added various marks and writings. The collections show us Pendleton as an editor and publisher, in a fairly straightforward sense: DABA is, indeed, his own press, through which he recently republished concrete poet Norman H. Pritchard’s remarkable 1971 book EECCHHOOEESS. They also remind us of the radical sort of influence a publisher can have, not just on content but on the very outlines of a given discipline. Pendleton believes that you cannot really understand painting unless you understand improvisation, and you cannot really understand improvisation without a thorough knowledge of poetry and music. Nor will you comprehend lyricism unless you comprehend the intersections of political struggle and love.

This is not mere argumentation; this is an attempt to reengineer the ways in which published writing is associated with the experience of viewing art. Similarly, the physical work Pendleton creates is designed not merely to exist within but to affect the feeling and meaning of the institution housing it. As curator Stuart Comer notes in the preface to Who Is Queen?, the exhibition at MoMA “recalibrates the museum, from a rigid frame designed to regulate official accounts of history into an open, generative, and polyphonic device.” Pendleton has constructed an architectural installation in MoMA’s atrium, with three five-story wooden scaffold towers painted black. The towers mimic balloon frame construction, a method for building homes popular in the US from the 1880s to 1930s; it was simpler and faster than timber frame construction, which required knowledge of complex joinery techniques. These physical frames evoke larger questions regarding housing availability in the US, as well as ad hoc forms of architecture associated with protest: Resurrection City, for example, constructed on the National Mall in 1968 during the Poor People’s Campaign, as well as the encampments of the Occupy movement and plywood boards transformed with spray paint by Black Lives Matter protesters. One might also see a link to the design experiments and architecture of modernism, from El Lissitzky’s 1923 Proun Room to Le Corbusier’s grid-like structures. Pendleton employs the towers as supports for a variety of artworks and devices, including paintings, graphic and textile works, sculptures, screens for moving images, and speakers for a sound piece, as well as a site for events. The exhibition is a powerful Gesamtkunstwerk, or all-embracing art form, with Pendleton signaling to viewers in many different registers and media.

Pendleton has transformed the space at the heart of one of the most influential institutions in the world, calling to mind a related watershed essay. In “On the Museum’s Ruins” (1980), critic Douglas Crimp describes Robert Rauschenberg’s painting practice as “insisting upon the radically different kinds of picture surfaces upon which different kinds of data can be accumulated and organized,” and points to its affiliation with “discontinuity, rupture, threshold, limit, series, and transformation,” as opposed to historical continuity. In Crimp’s reading, Rauschenberg’s photographic layering, via silkscreen, of canonical artworks—“Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus and Rubens’s Venus at Her Toilet”—is emblematic of a new logic of pictures in an era of near-instant reproducibility and dissemination: singular physical art objects lose their value and qualities as such, and become instead “‘moments’ of art.”

Crimp’s discussion of a movement from emphasis on discrete objects to emphasis on flashes of time seems quite relevant to Pendleton’s practice. But while Rauschenberg explored numerous disciplines and media, beginning his career as a choreographer before turning to assemblage and graphic work, Pendleton is determined to combine an equally multifarious résumé into a single piece, as “Who Is Queen?” makes manifest. There is a larger gambit here to dispense with specialized audiences—readers of poetry, appreciators of sound art, and so on—in order to create a new sort of public, one for whom experiencing multiple artistic disciplines at once is illuminating and desirable. Pendleton seems to believe that we need as many points of access to our history as possible, so he aims to reform not just objects and space, but the very sensory and temporal conditions under which we consume art and other media.

How does Pendleton generate these revised sensory and temporal conditions? A simple answer is: research. As suggested above, these conditions have much to do with that queen of his studio, the copy machine, along with his library of books, and the surfaces and features of the studio itself. It takes a relatively short time to remove a book from a shelf, and a few more moments to then sit and find a page, to stand and go to a copier to reproduce it. Yet, in Pendleton’s practice, these everyday acts of study and reflection, which are also acts of love, traverse much broader expanses of time and space. They recur as moments of viewing and listening in galleries, with pages altered, blown up, and reframed; with pieces of language excerpted and recopied; with new interventions and participants added. Pendleton’s research is amplified by institutions and yet it reframes the location it occupies. His installations resonate with a larger, always-unfinished collection of texts, images, and performances the artist continually mines for republication.

Thus, publication might be a useful way to think about all the work Pendleton makes, and using a term with an industrial history reminds us of the role technology plays in this undertaking. Of the title of his MoMA installation, Pendleton has said,

Queen is a kind of Afro-optimism balanced by a kind of Afro-pessimism, and it’s also a kind of queer theory. Queen is all about being queer, really, the perpetually misunderstood position. It’s about this memory of someone saying to me, years ago, when I thought I had done away with such things, ‘Oh, you’re such a queen.’ It really came out of this feeling or this sense of vulnerability, when someone thinks that they can name you or claim you as something, even if at any given moment it’s not what you might have wanted to be.

With his new books and his work in the museum, Pendleton makes public myriad texts, contexts, histories, and presents, seeking to outpace and overwhelm others’ limiting claims. He helps us look at space (and the contemporary world) through books and then look at books and their pages in a new light. This comparative gesture, the gesture of the publisher, comes with an important difference: traditional authorship has receded, replaced by an alternate and far more vulnerable practice, a practice that remains as open as a dance floor, even as it is contested, haunted, many-voiced, thick with marks. For, as Pendleton has said: “I am both in control and not.”

Date: September 23, 2021

Publisher: Art in America

Format: Print, web

Genre: Nonfiction

Link to the essay.

This essay appears in the November/December 2021 print issue of Art in America, with the title, "The Artist as Publisher: Adam Pendleton's recent book projects suggest that his multidisciplinary practice is also a kind of anthology."

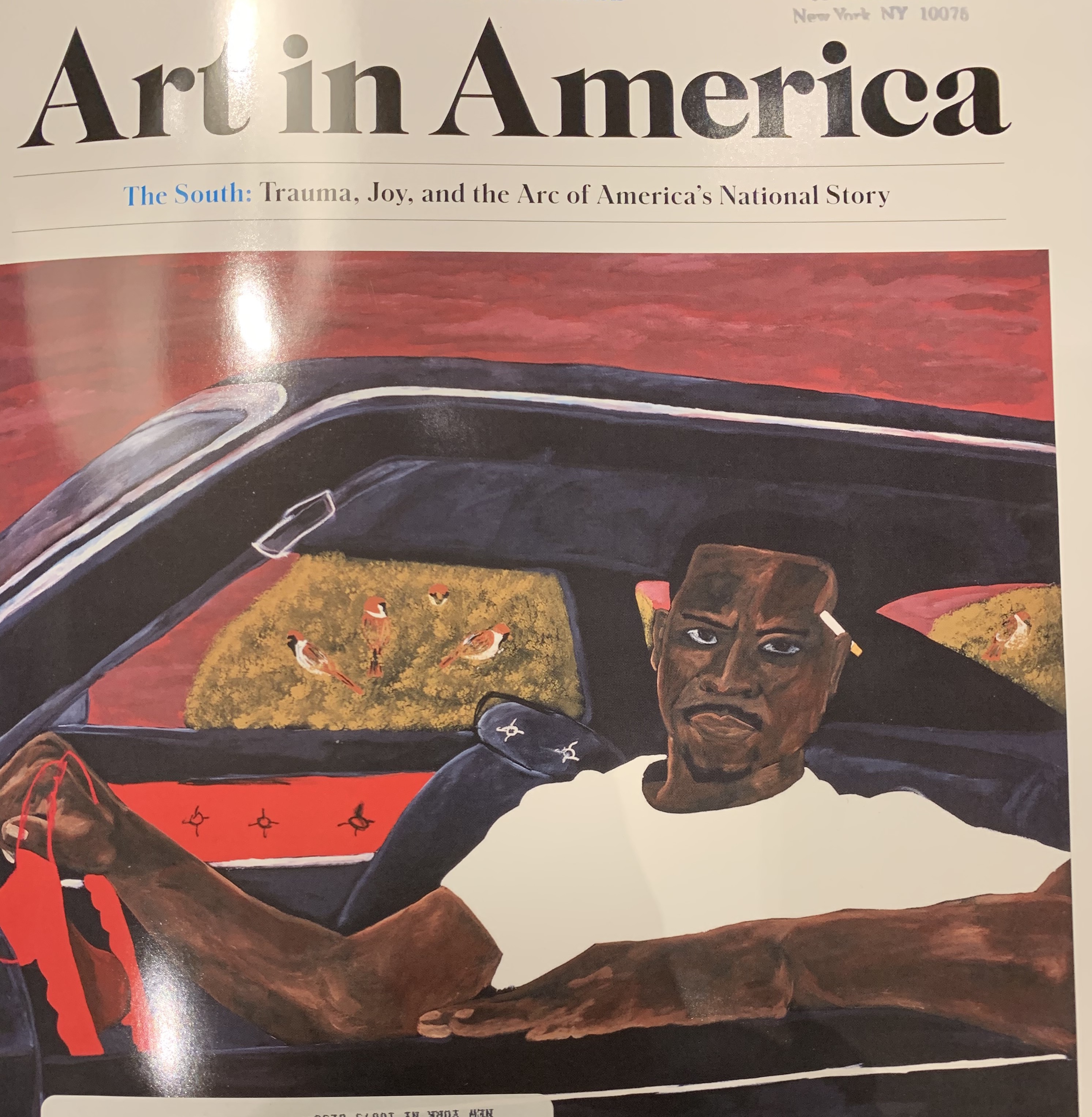

Cover.

Article in print.