THERE ONCE WAS A PERSON WHO COULD DRAW ANYTHING

Il est surnaturel d’arrêter le temps.

– Simone Weil, Notes for Venise sauvée

At her 1943 death, the philosopher Simone Weil left unfinished a ‘tragedy in three acts’, Venise sauvée, or Venice Saved. This play about an averted coup is gorgeously, strangely formal and slow—a dramatic rendition of an actual early seventeenth-century incursion. Short on dialogue, Weil’s draft is studded throughout with plans for future writing, including description of the exact number of syllables of blank verse to be assigned to various characters. At the play’s close—one relatively complete section—the naïve heroine Violetta declaims a poem. Ignorant of the plot to destroy Venice as well as the role of her own beauty in the collapse of this nefarious design, she murmurs, ‘Qu’il sont beaux sur la mer, / Les rayons du jour!’ (How beautiful they are on the sea, / These bands of daylight!) Offstage, revenge killings ensue, but neither Violetta nor the vast majority of the Venetians know anything of this. The denouement of Venise sauvée envisions a mostly static and unreal scene in which nothing happens save that some light travels. Venice is unaware that it has been saved. And any appreciation of light at the end of this drama does not come with added symbolism. The light is simply present. As critic Anne-Lise François wryly describes this moment, ‘Venice awakens to a beauty it has not lost the power to take for granted’.

In François’s reading of Venise sauvée, Simone Weil has created a play that fails to conform to the rules of Aristotelian tragedy, lacking a convulsive final moment of reversal and recognition. Weil’s play is ‘the (non)record of events that failed to transpire’. In other words, it records non-existent events of a plot that does not unfold. It displays the trace of a transformative will that in fact recedes curiously from the stage, rather than setting narrative in motion. The tragic hero Jaffier, who might have ruined Venice, hesitates to enact Venice’s destruction for no particular reason other than that the city actually exists—and he notices this. After he is betrayed by those to whom he has confessed, Jaffier makes a desperate petition to the sun, sky, ocean, Venetian canals, and blocks of marble. He describes these inanimate things, calls their names and curses them, but to no avail. The historical event collapses inexorably, quietly and mechanically, on his head.

If not strictly speaking a play in which nothing happens, Venise sauvée is a play in which the mystery of the physical existence of the world—one’s surprise, for example, that there is a world at all—has the power to interrupt the history of mankind. Lest this be understood as some form of primal ontological surprise, Weil uses the term ‘surnaturel’ to describe Jaffier’s decision not to act; his choice to instead, as she puts it, ‘stop time’. ‘Il est surnaturel d’arrêter le temps’, Weil writes in a contemporary notebook, regarding Jaffier’s retreat. And she repeats the term, instructing herself, ‘Faire sentir que le recul de Jaffier est surnaturel’. (Give the impression that Jaffier’s retreat is supernatural.) This, according to Weil, is a moment at which eternity enters human time.

Begun in 1940, Venise sauvée is also a complex comment on Paris’s fate under the Vichy state. The play is now infrequently staged, not least because of its incompleteness. And it is indeed difficult to think of a proper theatre and audience for its arabesques of meditative avoidance of action, leading to a non-event including lovely light. Yet, if there is such a theatre and such a setting, it might well be the Serralves Villa, as reimagined in the 2017 exhibition of artist Nick Mauss. With long bands of daylight striping the walls and floors, accompanied by equally expressive passages of shadow, the Villa lushly affirms its own existence. Its citations of classical architecture, along with its modern styling, suggest a complex and highly civilized relationship to the notion of history. Mauss’s sculptural and pictorial arrangements in the space at once reflect the aesthetic lineages in which the Villa’s design participates and challenge its claims to orthodoxy. Mauss’s work—like the sight of Venice imagined in Venice sauvée—and like the tragic hero’s miraculous recognition of the bare and actual existence of the great city—is a supernatural incision in everyday time and space. It permits the visitor access, if not to eternity, then to other planes of vision. Additional pictures, patterns, and outlines now appear within the Serralves Villa. These might underlie or be implicit within the Villa’s rooms. They may be excavations of form dormant in the Villa’s design. They may also simply be possible.

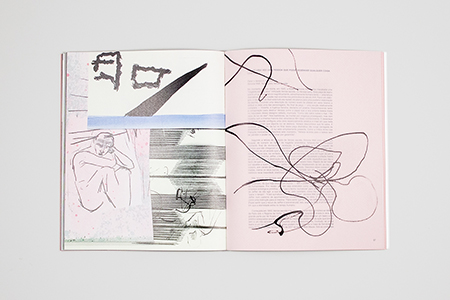

Mauss’s work plays with our expectations regarding surface. The image of what appears to be a pencil sketch has been enlarged in steel. It rests solidly against a wall. One feels a foolish urge to rush over and attempt to fold it in half. Surely it will resist. And yet one now feels an identical urge, with respect to the immaterial shadow cast by this sculptural form. The act in question is equally impossible.

Elsewhere, Mauss’s lines skitter across the speckled surface of a mirror. Intimate figures form. We must place ourselves conscientiously, depending on our willingness or unwillingness to be included, to have our own bodies potentially interrupt (or join) this scene.

The use of printed fabric, too, is a way of disrupting commonplace relationships to the surface on which a picture rests. Patterning, repetition; these gestures trouble the primacy of a single image. Indeed, the print on fabric threatens to become merely decorative, a drape or unrealized garment. It refuses the high seriousness of portraiture. It will not ‘look back’ at the viewer.

Everywhere there is a tension with, if not outright opposition to, lyrical treatment of history. Indeed, this is a tension Weil herself certainly felt. The various rooms and passageways are not explained with recourse to personal histories of the Villa’s creators or owners; no masterful design history stuns us into awed attention with its authoritative detail. Rather, the Villa is engaged as a varied surface, a permeable given. (How beautiful they are…, / These bands of daylight!) Everything we notice here, we are asked to notice as if we have already been looking at it. Everything is new, because we had not yet recognized that we had already been seeing it. The power to take this extraordinary home for granted (a power we never knew we possessed) is returned to us. The question that remains is, what will we do with this weightless liberty?

I do not pose the above question idly. For of course this art making is also occurring in the present of 2017, a historical moment of so outlandish a form that it begs for reconciliation with some era or event of the past. But my citation of Simone Weil’s citation of a 1618 intrigue in Venice as a citation of 1940s occupied France is not intended to serve as a complex analogue for the contemporary. Rather, I cite Weil because she seems to have observed something about the nature of the claims we make about the meaning of history, and I find her observation not merely relevant in a general contemporary sense, but relevant to Nick Mauss’s work, in particular.

The Serralves Villa contains numerous images of itself, numerous reflections, within it. These change with the changing time of day and the passage of visitors. These images are visual and kinetic, created by the elaborations of the sun, moon, and other external and internal sources of light; they are sonic, as when the Villa’s rooms reverberate with voices and footfalls. Clearly there are numerous examples of the way in which the Villa multiplies itself internally, by way of images produced by the coincidence of society and the physical world. (How beautiful they are…!)

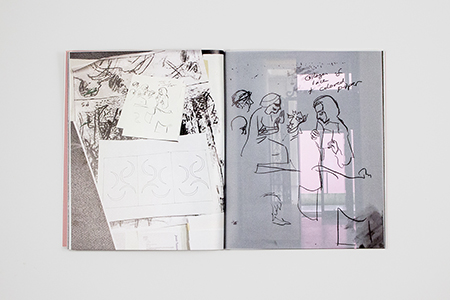

Mauss’s response to these images is to admit their existence. But he does not reproduce them, holding them up so that we may step into a romantic dioramic recreation of the scene we already inhabit. He does not elaborate images in such a way that we are shocked or amazed by the accuracy of his gesture. Rather, his drawing—for much of his work, even the work that is not explicitly drawing, is drawing, and he is a person who can draw anything—favours a recessive articulation. To the viewer he offers a line that takes the form of a beautiful event that the viewer does not know he or she has not lost the power to take for granted.

One example of this mode of articulation are the dance figures Mauss has also included in the exhibition. What could be more artificial than these representations, with their unusual, typographically performative arrangements of text? And yet they are participatory images; they show and tell us what will happen, should we dance. They are not representations of dances, they are dances. In this sense, they recede from the eye as drawings and come to seem more like speech or gestures, i.e., the dances that they are. Of course, these dance figures are not original drawings by Mauss; they are reproductions. Their status as reproductions of historical texts intensifies our experience of Mauss’s line as one in retreat. He has not quite written these words, although he has also not quite not written them.

Similarly, the shifting locations and material statuses of the surfaces on which Mauss writes and draws contribute to our sense of his mode of drawing as a deliberate retreat from a kind of drawing that could be claimed or exploited, as such. In spite of this retreat, his drawings hardly cease to appear. They become ever more durable, more multiple, more fascinating, and more ubiquitous. The non-existent white ground of the so-called pencil sketch enlarged in steel I whimsically pretended to wish to bend earlier causes the viewer to attempt to compose a picture using a support that flickers in and out of view. One focuses, erroneously and even a little hilariously, on a white “page” that is in fact a wall. The act of perceiving the steel sketch itself may even become lost in this flickering deliberation.

To return to my earlier contentions regarding Weil’s treatment of history, her personal dedication to participation and empathy, along with her extraordinary capacity for study, suggest that the recessive action of Venise sauvée stands in deliberate contrast to hasty heroic and/or violent solutions to political crisis. Yet, this does not mean that the play ignores the existence of political crises or their seriousness and insolubility. Without idealizing human nature, the play imagines a place and a role in the material world for human nature—and ties this place and role to human politics. The play imagines that one way human consciousness and creativity can function is as a labour of ensuring that the ongoing human appreciation of beauty—a sometimes unconscious appreciation we all hope to have the luck of not needing to be reminded of by way of crushing deprivation, harm, or disaster—can merely continue.

I imagine that a staging of Venise sauvée among the rooms and passageways of the Serralves Villa in which Nick Mauss has staged his various modes of drawing (and withdrawing) would be an echoing, choral affair. I wonder if Mauss would consider contributing a setting for the play’s final poem. Perhaps there is some way of indicating what Weil has conceived of as nearly un-representable events: those sunbeams on water that turn out not to be anything more or less than sunbeams on water. Or perhaps the entire play could be revised to consist in the enactment of that single sentence of appreciative pleasure. I should say that this, at any rate, is what I think of Nick Mauss’s work as already accomplishing.

*

NB: Discussion of Simone Weil’s unfinished play, Venise sauvée, in this essay is deeply indebted to Anne-Lise François’s brilliant writing in Open Secrets: The Literature of Uncounted Experience.

Date: June 22, 2017

Publisher: Museu de Arte Contemporâneo de Serralves

Format: Print

Genre: Nonfiction

Intricate Others.

Intricate Others.