YEARS AGO BEFORE THE NATION WENT BANKRUPT

An introduction to the journals of David Wojnarowicz

Artist David Wojnarowicz’s thirty or so journals are stored in a pair of boxes in New York University’s Fales Library. Folders of loose photographs, tickets, and postcards are also included, as is an oversize wall calendar, sparsely annotated by Wojnarowicz, of the type one might find in the gift shop of the American Museum of Natural History (triceratops rooting in lush surrounds). “Series 1,” as this lot of the David Wojnarowicz Collection is designated, feels like a grouping of keepsakes: These are items in and by means of which Wojnarowicz marked, from 1970 to 1991, time’s passing. In 1992, he died at the age of thirty-seven.

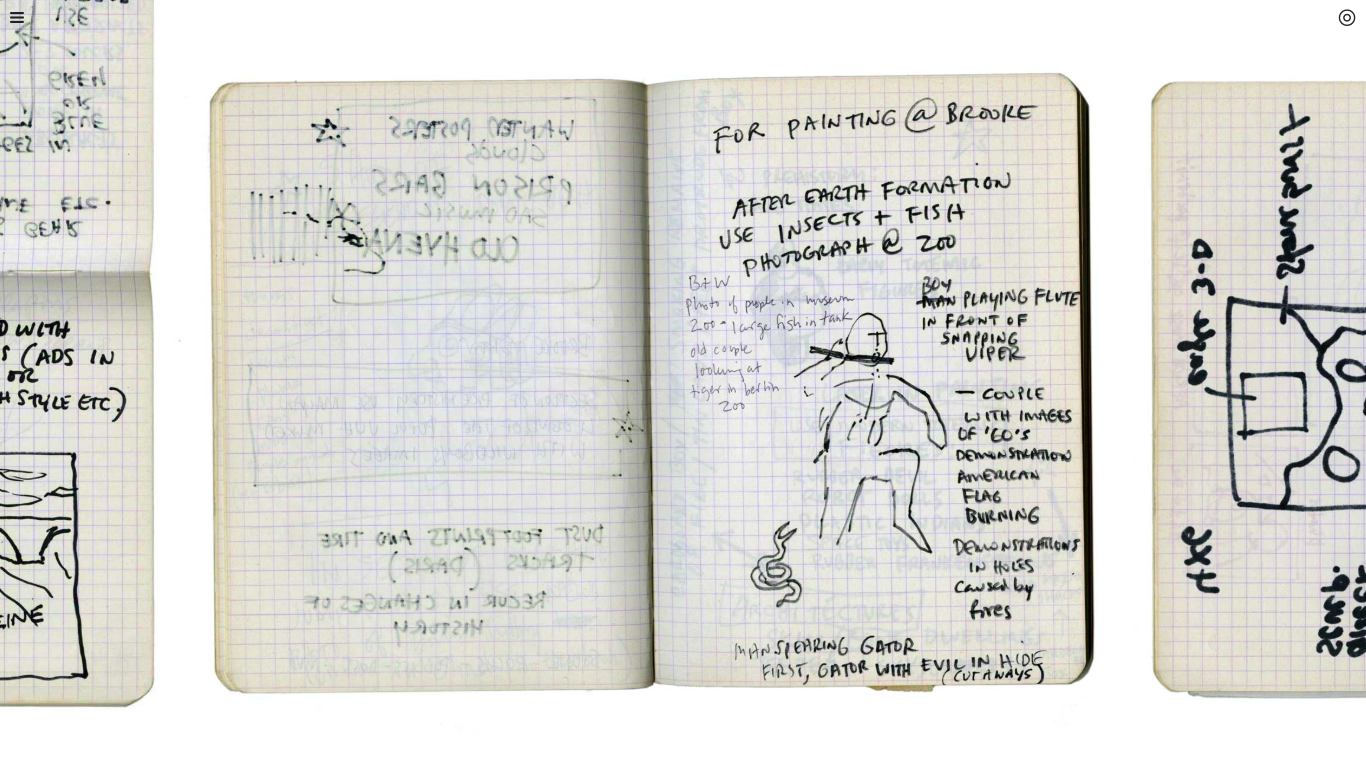

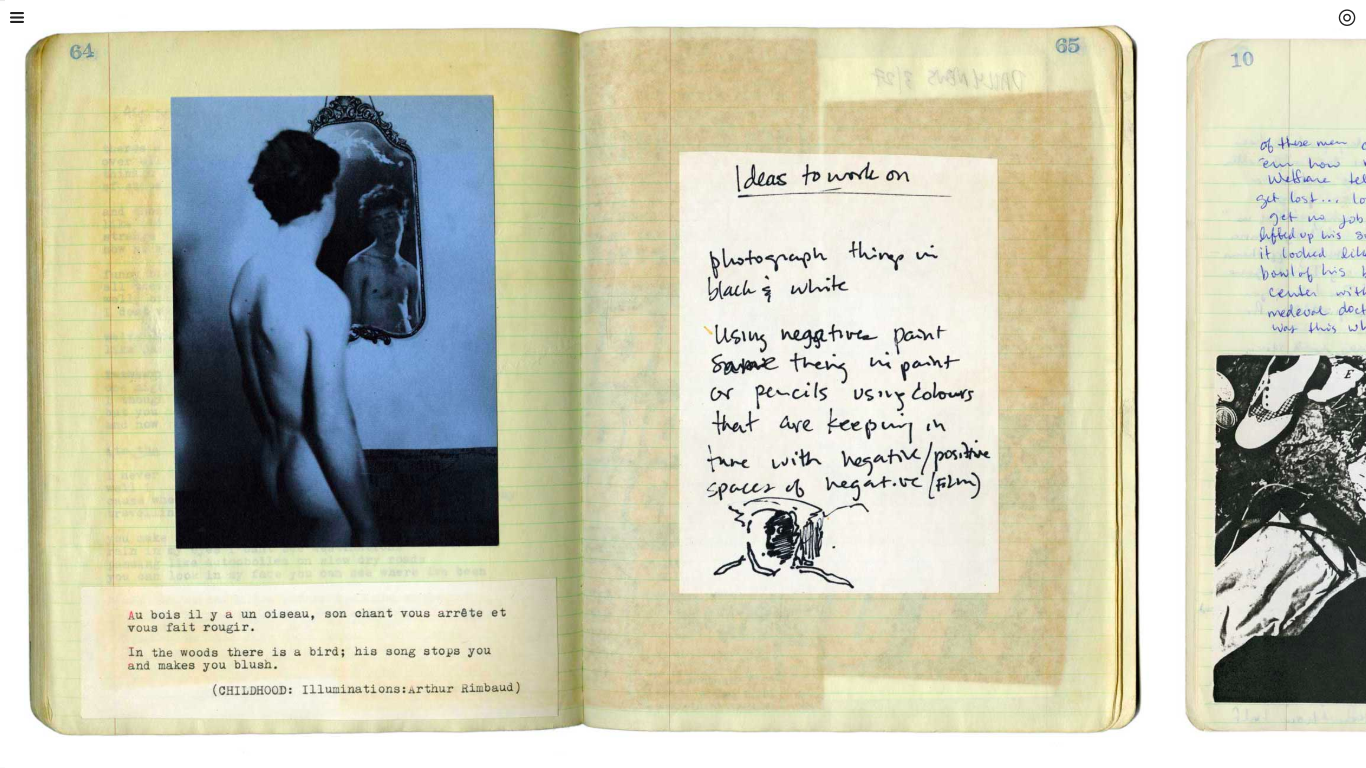

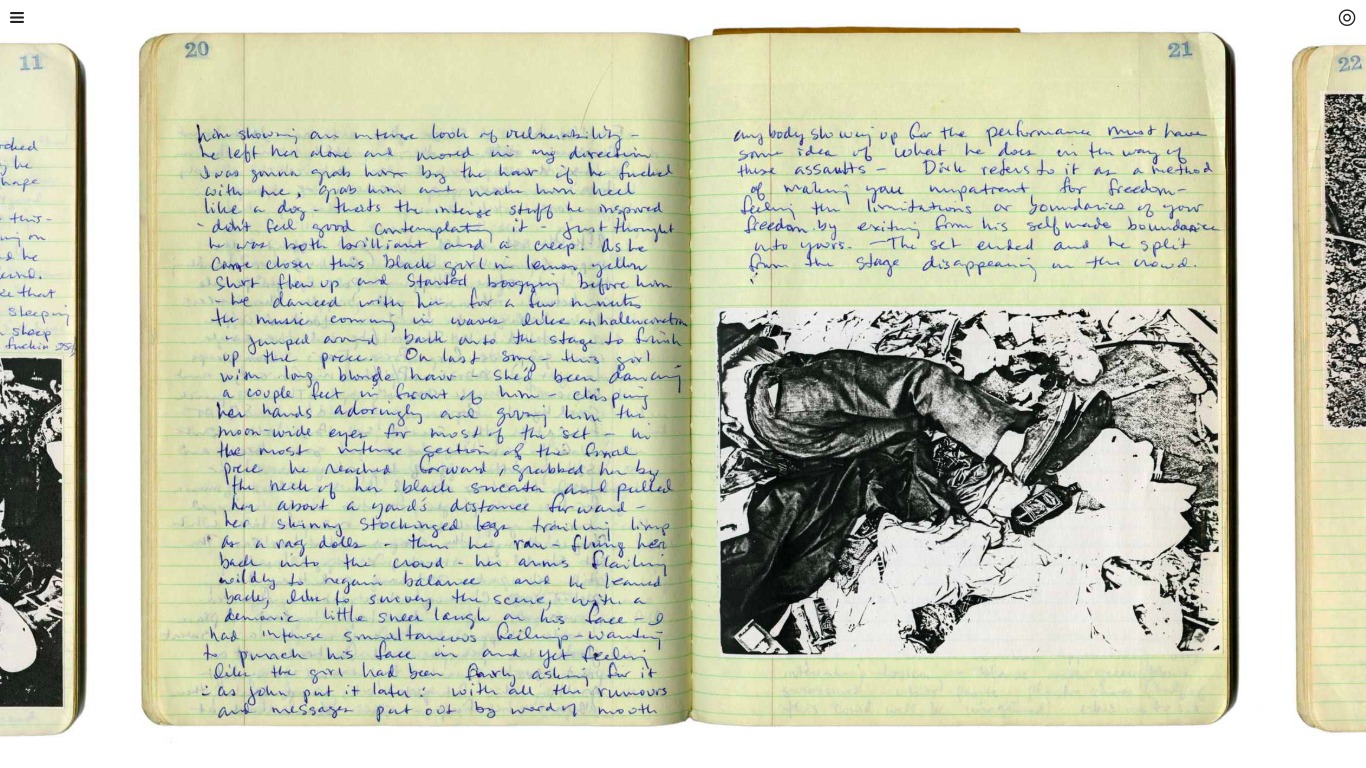

The journals were also meant for publication and display. Composition books predominate, though there are larger spiral-bound notebooks and one three-ring binder. The covers are occasionally embellished with collage or a holographic sticker. Wojnarowicz interleaves clippings, print ads, band flyers. Pages are pasted over with typescript, newsprint, photocopies of photographs, handwritten notes, redacted poems. The journals were a location in which Wojnarowicz prepared—by means of plans, lists, sketches—work he would later execute in other media, and they were also a site for work. As they themselves self-consciously narrate, these books were a constant in the practice of a peripatetic artist who painted out of doors, who traveled, who regarded homelessness as inherent to humanity (what in one entry he refers to as “the matter of having no home”).

Wojnarowicz made extensive use of the text of his journals, excerpting and reworking sections to create essayistic pieces that appear in Close to the Knives and Memories That Smell like Gasoline. He wrote with his body as witness, vehicle, and recording device: For The Waterfront Journals, for instance, he conducted interviews with people he met on the streets of American cities before “transcribing” monologues from memory, perhaps fictionalizing. In this sense, the kinds of experience with which Wojnarowicz was concerned could not be rendered untrue by the embroidery of art; as the artist once said in an interview with Nan Goldin, “I grew up realizing and believing there’s no difference between fantasy and reality. I always believed that my fantasies were stored pieces of information.”[1]

This belief in fantasy as “stored … information” might inform our reading of the journals, for the writing here seems searingly honest and committed to the actual even as it is devoted to its own language and to the unreal concerns of literature—to symbolism, imagery, dream, erotic transport, and even a kind of lyric thought or philosophy of the self.

Of his diary accounts of sex at the West Side piers and elsewhere, Wojnarowicz told Sylvère Lotringer:

When I wrote them I was so excited to write them, to document them. I thought they were the most amazing things that I had ever seen. They were like films or they reminded me of Burroughs’s Wild Boys. I loved it. I loved the fact that it was outdoors, that it was by the river and in the wind. They were moments of incredible beauty to me.

I remember when I first started becoming more and more aware of AIDS. And here I am sitting with all these journals, looking at them in total disgust. … And now, years later, I realize I shifted again and want these things.[2]

It is with this in mind that one reads Wojnarowicz’s accounts of anonymous sex, his cinematic reflection of the encounter. Many of the selections I have made here, then, are graphic—perhaps more so than other previously published excerpts from the journals. There are also mundane episodes. We see a Manhattan that barely resembles our own. And we see Wojnarowicz at work, taking photos of hell in an alley (homelessness, refuse) or visiting an editor at the Soho Weekly News, the paper that would first publish his “Rimbaud in New York” series. I have wanted to show both the explicitness and the everydayness of Wojnarowicz’s writing practice, as it is in this meeting of the extraordinary and the routine that one finds the crucible of the artist’s personal myth.

I have also included “Dateline for Retrospective Catalog.” This sketch, written in list form, is a draft of a text that appeared in a catalogue of Wojnarowicz’s work from 1979 to 1990, Tongues of Flame. The published work, in paragraphs, is titled “Biographical Dateline,” and it expands the outline’s pithy notes. For example, what in the preparatory document is “Stabbed Steven: lizard tail in hand in police station” becomes, in “Biographical Dateline,”

Stabbed my brother in a fight back in n.y.c.—while waiting for the police to arrive at the apartment to take me away I played with my lizards. One of them dropped the tail off in a self-defense move. The tail continues wiggling for twenty minutes or so to confuse the predator. In the police station a cop asked me what I had in my hand. I replied, a lizard tail. Cops thought I’d gone over the edge.

If the draft “Dateline for Retrospective Catalog” lacks detail and standard syntax, it makes up for this in economy of expression, as a sort of episodic poem.

There is much that has been left out. Without mentioning the mass of writing and illustration that remains unpublished in the journals, it has also not been possible to preserve all of Wojnarowicz’s handwritten punctuation, his use of ellipses, spaces, and dashes of varying length. For this reason, one may look forward to Fales’s completion of a digitization project of the journals, at which time these will be viewable in their entirety online. (Additionally, from November 18 of this year until February 12, 2012, the Brooklyn Museum will host the exhibition “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” formerly presented at the National Portrait Gallery, here emphatically including Wojnarowicz’s 1985–87 film A Fire in My Belly.)

Date: September 23, 2011

Publisher: Triple Canopy

Format: Web

Genre: Nonfiction, biography

Link to the introduction.

This piece includes transcriptions and images from the journals of David Wojnarowicz, housed at Fales Library at NYU. The text at left serves as an introduction to the selection, made in summer of 2011 for issue 14 of Triple Canopy, "Counterfactuals."

Journal image.

Journal image.

Journal image.

- “Nan Goldin/David Wojnarowicz,” in David Wojnarowicz: A Definitive History of Five or Six Years on the Lower East Side, ed. Giancarlo Ambrosino (New York: Semiotext[e], 2006), 202.

- “Sylvère Lotringer/David Wojnarowicz,” in Ambrosino, 194.